Jahng Calvin

Reporting quality of evidence synthesis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): Examining articles that guide treatment recommendations

April 29, 2020 in College of Pharmacy, Virtual Poster Session Spring 2020

Purpose: Evidence synthesis can be helpful in the development of evidence-based guidelines. Examples include article types such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, just because evidence synthesis is included in guidelines, doesn’t mean that article is of good quality. We aim to assess reporting quality, one dimension of an article’s overall quality, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). We will determine if evidence synthesis citations in the Department of Health and Human Services human immunodeficiency virus guidelines follow trends for poor reporting quality or if they constitute a benchmark for the best evidence available in HIV.

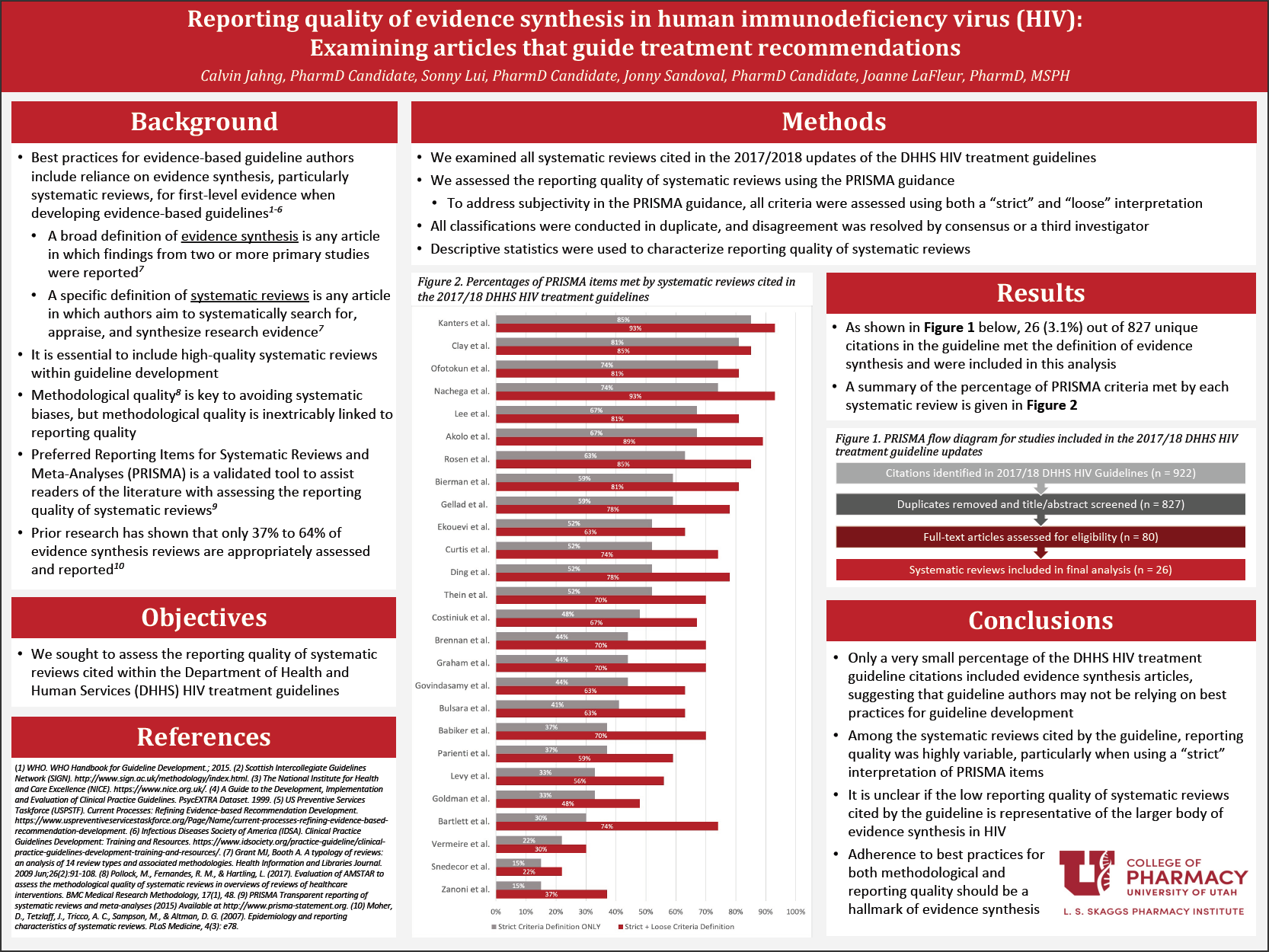

Methods: Pubmed citations for all articles cited in the 2017 and 2018 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) human immune deficiency virus (HIV) treatment guidelines were entered into EndNote and duplicate citations were removed. 2 study investigators independently classified each citation as evidence synthesis or not using the title and/or abstract, defining evidence synthesis as “any article in which the results of 2 or more primary studies were combined.” A third investigator resolved disagreement. For articles in which the reviewers could not make the classification using title/abstract only, the full text was reviewed. Articles that did not fit the study definition of evidence synthesis were excluded. A data collection form consisting of PRISMA criteria was created within the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) and used by 2 investigators to independently perform a full-text review of the articles that met inclusion criteria. Disagreement was resolved by consensus/a third party. Data analyses consisted of frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations with confidence intervals calculated appropriately.

Results: A total of 26 articles were included in the final analysis. No article included 100% of the items developed by PRISMA, with a range of 15% to 85% in regard to the strict criteria only. When looking at strict and loose interpretations of the criteria combined together, the range became 22% to 93%. When each individual PRISMA item was considered, the top three best performing items included topics regarding justifying the reasoning for conducting the systematic review, authors’ reporting of pooled results, and describing findings in the context of other research. The bottom three performing items included topics regarding describing authors’ methods of assessing study-level risk of bias, assessment of review-level risk of bias, and reference to a review protocol.

Conclusion: Within our corpus of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, reporting quality based on established PRISMA criteria varies greatly, with some articles reporting as high as 85% and as low as 15% of total items. It is evident that, although these types of studies are considered the highest possible level of evidence, it may not necessarily mean that they are of good quality. Critical appraisal is still a necessary element in determining if a study should be used as a recommendation reference. Until more guidance is developed, readers should be aware that a rigorous evaluation of an article is still a necessary practice.